What is empathy?

Empathy is the capacity to understand and acknowledge other people’s feelings, thoughts and behavior. It is usually characterized as an emotional reaction to other people’s emotions, usually when they are in a state of distress. Empathy means the ability to feel and understand another person’s inner world as if it were our own world, but without losing track of our own selves. It is the ability to experience the mental, emotional and behavioral state of another person, while completely separating ourselves from that person. In other words, it is a person’s ability to offer support by “stepping into someone’s shoes” temporarily, not out of identification with the other person, but out of an understanding of their difficulties and emotions.

Empathy develops based on a capacity called mentalization – a social cognition that allows us to visualize the desires, feelings, needs, and goals of others and of ourselves. Children who grow up in a non-validating environment and are not given the opportunity to express their feelings in an open and accepting manner, and who receive the sometimes unconscious message that there is no place for “non-functional” emotions and thoughts, will struggle to develop a capacity for mentalization, to understand their own mental states and those of others, and to separate emotions.

Empathy is one of the most important social skills for a person who wishes to maintain social relationships. When we are able to empathize with our friends, we can understand situations that do not necessarily correlate with our current emotional state, and offer support them nonetheless.

In arguments between friends, each side tends to perceive the situation from a different point of view and may find it difficult to acknowledge the different thoughts and emotions of others, especially if the subject overwhelms them emotionally. The goal of therapy is to succeed in expanding the patient’s ability to apply mentalization even in emotionally intense situations. This is done by helping patients identify their thoughts, emotions, and beliefs in such situations, and examine how they affect their behavior.

Children with limited capacity for empathy often have a hard time maintaining friendships, since they fail to recognize the feelings of others and therefore can’t attain closeness or a sense of mutuality.

The Playing CBT cards give users the opportunity to practice mentalization.

For example, I had a 10-year-old patient with difficulties with her social skills. She struggled to understand her own inner world, as well as the inner world of others.

The girl described a fight she had with her friend because she had disappointed that friend. I asked her to tell me the story using cards:

At this stage we dealt with the personal experience of the girl who received the gift. Together we examined the reason for her reaction, her thoughts and feelings. The ability to examine these elements does not come naturally to children who have difficulty with mentalization, since they have trouble identifying and examining their own inner experience. Often, when a patient finds it difficult to examine their experience, I begin with a story that enables them to dissociate from the experience and hence examine it (usually through comics). Then I let them examine their experience based on this externalization model we jointly created.

The next step in our session was to develop the ability to recognize that someone else feels differently and thinks differently.

We took the cards again and I asked her to write down the same story, but this time from her friend’s perspective.

Therapist: “So, now that we’re sitting here, examining this, are you able to see that your friend felt and thought differently from you?”

Patient: “Yes, now I understand that she was offended too, and I must have misinterpreted her intentions. But at that moment it was very hard for me to see it because I was too hurt.”

Therapist: “Do you remember why you were hurt?”

Patient: “Yes, because I thought that I wasn’t important enough to her and therefore she didn’t put enough thought into my present. Maybe she did put a lot of thought and effort, but I jumped to wrong conclusions and tried to run away from the situation”.

Therapist: “So, what will you do next time?”

Patient: “Wow, I’m not sure. Maybe next time I’ll be able to stop for a moment, examine my thoughts, feelings and physical sensation , take a couple of deep breaths, and remember that my thought is not necessarily true.

Therapist: “Definitely. And maybe understand that your friend has a story of her own?”

Patient: “Right…”

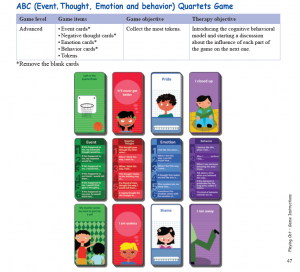

You may also use the quartets game (game no 11) to practice the model and teach about the different elements of the cognitive behavioral model, which will contribute to the development of the child’s ability to understand his/her personal experience as well as the experience of others.